|

||||

FORMAT FAMILIAL |

VIDEOS |

|||||

Why Walk When You Can Stroll?

Le sperme français de moins bonne qualité, selon les Britanniques Le nombre de spermatozoïdes des hommes français ont chuté d'un tiers entre 1989 et 2005, indique une étude.

http://www.slate.fr/lien/65761/sperme-francais-qualite

"I liked to shoot women pushing prams" Secret Nazi tapes shocking Germany

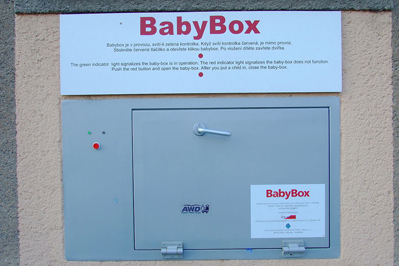

mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/secret-nazi-tapes-shocking-germany -L'ONU s'inquiète des «boîtes à bébé» où les Européens abandonnent anonymement leurs enfants http://www.slate.fr/lien/57529/baby-box-tour-abandon-bebe-enfant-europe-onu

-Polémique autour d’un projet d’impôt sur les Allemands sans enfant - (Les Echos 201216/2/2012) Afficher article

-Why Walk When You Can Stroll? http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/03/opinion/03scocca.html?_r=3&hp

Actually, that was an earlier stroller. The brakes wore out and the foot strap ripped apart under constant use. Now there is a new red hundred-and-something-dollar stroller on the shelf, which replaced that $69.99 stroller, which had replaced the $18 stroller we bought two cities ago, when the kid truly was incapable of walking. Tom Scocca is the author of the blog Scocca on Slate and the forthcoming “Beijing Welcomes You: Unveiling the Capital City of the Future.”

-The Mystery of the Ghost Stroller Deepens

http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/17/the-mystery-of-the-ghost-stroller-deepens/?ref=nyregion Maybe the sight of a reporter nosing around with a notepad for Tuesday’s Big City column made the mysterious creator of Park Slope’s ghost stroller — a stroller painted white to look like a memorial — think the object had received more than enough attention. -Kid Crazy: Why We Exaggerate the Joys of Parenthood

http://healthland.time.com/2011/03/04/why-having-kids-is-foolish/ All parents know that having kids is a blessing — except when it's a nightmare of screaming fits, diapers, runny noses, wars over bedtimes and homework and clothes. To say nothing of bills too numerous to list. Some economists have argued that having kids is an economically silly investment; after all, it's cheaper to hire end-of-life care than to raise a child. Now comes new research showing that having kids is not only financially foolish but that kids literally make parents delusional. Researchers have known for some time that parents with minors who live at home report feeling calm significantly less often than than people who don't live with young children. Parents are also angrier and more depressed than nonparents — and each additional child makes them even angrier. Couples who choose not to have kids also have better, more satisfying marriages than couples who have kids. (More on Time.com: 5 Pregnancy Taboos Explained (or Debunked)) To be sure, all such evidence will never outweigh the desire to procreate, which is one of the most powerfully encoded urges built into our DNA. But a new paper shows that parents fool themselves into believing that having kids is more rewarding than it actually is. It turns out parents are in the grip of a giant illusion. The paper, which appears in the journal Psychological Science, presents the results of two studies conducted by Richard Eibach and Steven Mock, psychologists at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. The studies tested the hypothesis that “idealizing the emotional rewards of parenting helps parents to rationalize the financial costs of raising children.” Their hypothesis comes out of cognitive-dissonance theory, which suggests that people are highly motivated to justify, deny or rationalize to reduce the cognitive discomfort of holding conflicting ideas. Cognitive dissonance explains why our feelings can sometimes be paradoxically worse when something good happens or paradoxically better when something bad happens. For example, in one experiment conducted by a team led by psychologist Joel Cooper of Princeton, participants were asked to write heartless essays opposing funding for the disabled. When these participants were later told they were really compassionate — which should have made them feel better — they actually felt even worse because they had written the essays. (More on Time.com: Five Things for the New Mom Who Has Everything) Here's how cognitive-dissonance theory works when applied to parenting: having kids is an economic and emotional drain. It should make those who have kids feel worse. Instead, parents glorify their lives. They believe that the financial and emotional benefits of having children are significantly higher than they really are. To test their hypothesis, Eibach and Mock recruited 80 parents at public locations in the northeastern U.S. Forty-seven of the parents were women, and all had at least one child under 18. Eibach and Mock then split the participants into two groups. Those in the first group were asked to read U.S. Department of Agriculture data from 2004 showing that it costs an average middle-income family in the Northeast $193,680 to raise a child to the age of 18. The second group was asked to read the same data, but participants in that group also received information that adult children provide financial and other support to aging parents so that parents are often more financially secure in their later years than nonparents. Both groups then read eight statements about parenting and rated their agreement with those statements on a five-point scale from -2 (strongly disagree) to +2 (strongly agree). The statements included falsehoods like “Nonparents are more likely to be depressed than parents” and “Parents experience a lot more happiness and satisfaction in their lives compared to people who have never had children.” (More on Time.com: Five Ways to Stop Stressing) The results confirmed Eibach and Mock's hypothesis. Parents who read only the data showing how expensive kids are should have responded more negatively to parenting. But in fact they idealized parenting far more than those who were also given the information about the benefits of parenting later on. Why? For the same reason you keep spending money to fix up an old car when it just doesn't work — or keep investing in the same company when it's failing. Humans throw good money after bad all the time. When we have invested a lot in a choice that turns out to be bad, we're really inept at admitting that it didn't make rational sense. Other research has shown that we romanticize our relationships with spouses and partners significantly more when we believe we have sacrificed for them. We like TVs that we've spent a lot to buy even though our satisfaction is no lower when we watch a cheaper television set. To confirm their results, Eibach and Mock conducted a second experiment, this time with 60 parents. The second study was identical to the first but added a control group that got no information about parenting at all. The second experiment also added measures of participants' enjoyment of time spent with their kids and intentions to spend future time with them. And the subjects were asked to compare spending time with their children to spending time with their spouse or partner, spending time with their best friend, and spending time on a favorite hobby. Once again, those who read only about how expensive kids are idealized parenthood far more than those who read about both the costs and the benefits of raising children (and far more than the control group did). They were also significantly more likely to believe that spending time with kids is more rewarding than other activities, even though researchers have found that when you measure how rewarding parents found any given day spent with their children, they rated that day worse than they had expected to. (More on Time.com: 5 Little-Known Truths About American Sex Lives) Does this mean you shouldn't have kids? Yes — but you won't. Our national fantasy about the joys of parenting permeates the culture. Never mind that it wasn't always like this. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we thought nothing of requiring kids to get jobs even before they hit puberty. Few thought of it as abuse. Reformers helped change the system — and rightly so — so that children could be educated. But this created a conundrum. As Eibach and Mock write, “As children's economic value plummeted, their perceived emotional value rose, creating a new cultural model of childhood that [one researcher] aptly dubbed ‘the economically worthless but emotionally priceless child.'” Or, as the writer Jennifer Senior put it in a New York magazine article last summer, “Kids, in short, went from being our staffs to being our bosses.” Of course parents should be commended for one little thing they do: maintain the existence of humanity. I praise them for that, but I think they're both heroes and suckers. Follow my health columns on Twitter @JohnAshleyCloud

Laboratoire de Recherche Research Laboratory

ADN modifié-Sans Os / DNA modified-boneless Astronomie / Astronomy (F.Louvat)

|

|

|||||

| BOUTIQUE | ||||||

Credit E.D-2010 |

Partenaires |

A propos de Trashpram

|